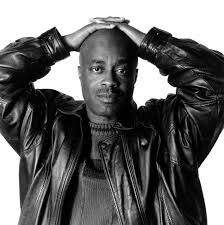

Jean-Dominique Bauby, who had lost the use of his limbs and voice, dictated his memoir, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, one letter at a time. Claude Mendibil, shown here as she transcribes, devised a time-saving system of reciting the letters of the alphabet for Bauby in order of their frequency in French words and waiting for him to blink in response.

Image via commons.wikimedia.org

In his book In Praise of Shadows, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki upholds the value of art that captures "the uncertainty of the mental process" rather than "neatly packaged conclusions."

Jean-Dominique Bauby's memoir, The Diving Bell and The Buttefly: A Memoir of Life in Death, makes use of this principle to describe the transformation Bauby underwent after a massive stroke left him unable to use his arms, legs, and voice. Here is the book's opening passage:

"Through the frayed curtain at my window, a wan glow announces the break of day. My heels hurt, my head weighs a ton, and something like a giant invisible diving bell holds my whole body prisoner. My room emerges slowly from the gloom. I linger over every item: photos of loved ones, my children’s drawings, posters, the little tin cyclist sent by a friend the day before the Paris-Roubaix bike race, and the IV pole hanging over the bed where I have been confined these past six months, like a hermit crab dug into his rock."

Jean-Dominique Bauby

The Diving Bell and The Buttefly: A Memoir of Life in Death

Translated by Jeremy Leggatt

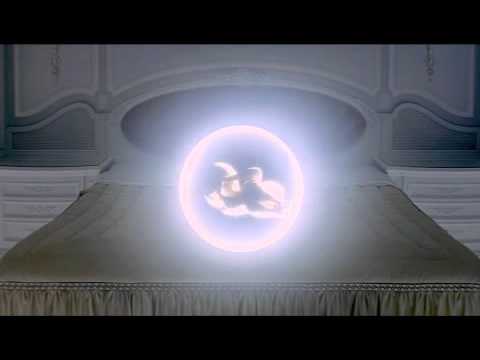

Note the reliance on images of confusion and uncertainty. Echoing Bauby's writing, Julian Schnabel's film version employs blurred lens focus and unexpected shot framing to convey Bauby's experience of first emerging from the coma after his stroke.

Note that the unknowing has been rendered clearly. The readers and viewers of these works will experience Bauby's initial confusion without being confused about whether they are correctly absorbing the material. Bauby and Schnabel have created portraits of confusion, not confusing portraits.

What is not known may be impossible to render, but our unknowing can nevertheless be rendered with precision.

Thank you for reading.