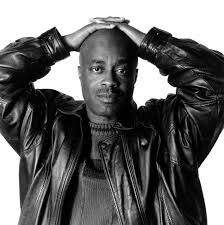

Charles Burnett. Image via blog.nwfilmforum.org.

In his classic book on acting, Audition, casting director Michael Shurtleff offers a series of twelve guideposts that help actors enrich their performance. The fifth of those is Opposites.

Whatever you decide is your motivation in the scene, the opposite of that is also true and should be in it . . .

Think about a human being: in all of us there exists love and there exists hate, there exists creativity and there exists an equal tendency toward self-destructiveness, there exists sleeping and waking, there exists night and there exists day, sunny moods and foul moods, a desire to love and a desire to kill. Since these extremities do exist in all of us, then they must also exist in each character in each scene. Not all opposites, of course, not this exhaustive listing I’ve just given, but some of them. If it is a love scene, there is bound to be hate in it too; if there is need, great need, for someone, we are bound to resent that need. Both emotions should be in the scene; it is lopsided and untrue if only one is.

Michael Shurtleff, Audition, pp. 77-78

We saw how this applies to narrative in our discussion of bridges, where one section of a song or book or film can challenge and thereby deepen the surrounding ideas.

Charles Burnett's masterpiece, Killer of Sheep, shows this principle in action, especially in its portrayal of children.

Note how these scenes are made richer by the opposites play and war. The games these children play are both fun and frightening. They have life-and-death hovering over them, which not only adds realism but also depth to our sense of their emotional life.

Thank you for reading.