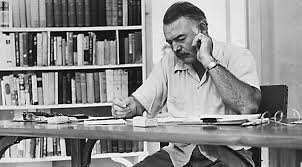

Hemingway is said to have aimed for 500 words a day. Image via www.authenticubatours.com

One of the biggest obstacles to creativity is a lack of self-entitlement. “Who am I to be here” in front of the computer, canvas, or on the stage? “I haven’t worked hard enough.”

A few years ago, I started logging my hours of writing and drumming. Here was some of what I learned:

- I was surprised to find how much work I actually do. My lazy self-image might say less my work ethic and more about my method of self-motivation.

- At times when I didn’t work, it helped to have a concrete sense of what a productive week can look like (which I had, thanks to my work logs).

- As a writer, I felt most free when I was most conscious of meeting my minimal work targets.

- As a drummer, I felt most confident on stage when I knew I had met my practice targets in the time leading up to the show.

- I always use a timer, which I stop during breaks so that the measurement has integrity. (On my computer, I use a program called Active Timer that tells me how much time I spent in any particular document (as opposed to time spent checking email, etc.)

- I set modest goals in order to build a rhythm of success instead of failure. (If you are wondering about the power of a regular modest output, consider that John Irving stops his writing day at three pages; Hemingway’s daily target is said to be 500 words. Multiply these small doses by 250 days and you can see that they add up.)

- I find that in weeks during which I work consistently, even when I fell short of daily targets, I end up producing better work. Working every day leaves me more limber. The hardest thing is to come back to work after an extended absence.

- The accumulation of the work logs whets my appetite for doing more work. I’m open to considering that this testifies to my twisted artist’s conscience, but I also know that we artists often need to find ways to trick ourselves into working. If keeping track of my work is one such trick, why not keep doing it?

Thank you for reading.