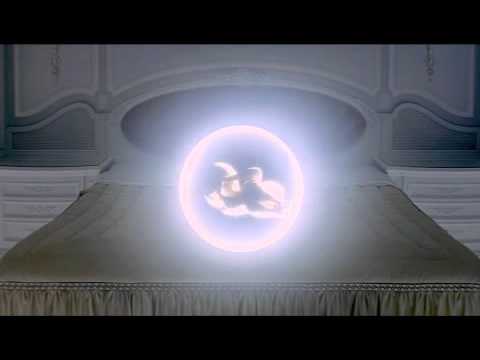

A more certain fate awaits Constantin, the condemned man in J. G. Ballard’s short story “End Game.” Constantin has been convicted of a crime and sentenced to death, but in this society, death sentences are carried out at an unspecified time. Constantine lives in a sequestered community with his executioner (his ‘supervisor’), Malek. The spend their days together. When Constantin falls briefly sick, Malek helps him recover. They play chess. Constantine learns that Malek knows the precise moment at which he is to carry out Constantine’s execution, though Malek will not divulge this information to Constantine, who must go on living never knowing which breath will be his last.

Drawing the lapels of the dressing gown around his chest, Constantin studied the board with a desultory eye. He noticed that Malek’s move appeared to be the first bad one he had made in all their games together, but he felt too tired to make the most of his opportunity. His brief speech to Malek, confirming all he believed, now left nothing more to be said. From now on whatever happened was up to Malek.

“Mr. Constantin.”

He turned in his chair and, to his surprise, saw the supervisor standing in the doorway, wearing his long gray overcaot.

“Malex—?” For a moment Constantin felt his heart gallop, and then controlled himself. “Malek, you’ve agreed at last, you’re going to take me to the Department?”

Malek shook his head, his eyes staring somberly at Contantin.

“Not exactly. I thought we might look at the garden, Mr. Constantin. A breath of fresh air, it will do you good.”

“Of course, Malek, it’s kind of you.” Constantin rose a little unsteadily to his feet, and tightened the cord of his dressing gown. “Pardon my wild hopes.” He tried to smile to Malek, but the supervisor sttod impassively by the door, hands in his overcoat pockets, his eyes lowered fractionally from Constantin’s face.

They went out onto the veranda toward the French windows. Outside the colde morning air whirled in frantic circles around the small stone yard, the leaves spiraling upward into the dark sky. To Constantin there seemed little point in going out into the garden, but Malek stood behind him, one hand on the latch.

“Malek.” Something made him turn and face the supervisor. “You do understand what I mean, when I say I am absolutely innocent. I know that.”

“Of course, Mr. Constantin.” The supervisor’s face was relaxed and almost genial. “I understand. When you know you are innocent, then you are guilty.”

His hand opened the veranda door onto the whirling leaves.

—The conclusion of "End Game" by J. G. Ballard

Note the sense of a crescendo interrupted. It suggests both Constantin’s death and the length of each second between now and that fateful moment.