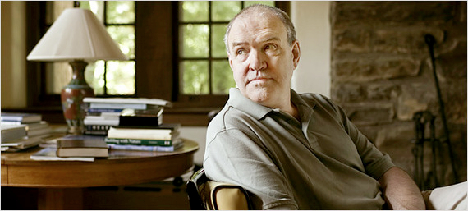

Dorsey Wright as Cleon, the leader of the Warriors. The Coney Island Wonder Wheel glows in the background. Image via pixshark.com.

Walter Hill’s 1979 film The Warriors, based on Sol Yurick’s novel, has a relatively simple premise: a street gang from Coney Island, the Warriors, must find their way home from the Bronx while being pursued by all the other gangs in the city, who wrongly suspect them of having murdered someone who was going to unite all of the city’s gangs.

The opening credits are shown over a seven-minute montage that brilliantly maps out the movie’s premise.

The film opens on a nighttime shot of a The Wonder Wheel, a Coney Island landmark.

Image via socialpsychol.wordpress.com.

A subway train pulls into a station, with the Wonder Wheel still in the background.

We see the Warriors board the train, intercut with a speech from their leader, Cleon, briefing them on the gathering they are about to attend.

Image via clothesonfilm.com.

As their subway train makes its way, we see other gangs getting on other trains, intercut with shots of gang members consulting subway maps. Even non-New Yorkers will get the idea that the Warriors are traveling from one end of the city to another. (For cinematic reasons, the film proceeds to take great liberties with the geography of NYC's subway lines.)

Images via thewarriors.wikia.com and pyxurz.blogspot.com.

Finally, we see a wide shot of hundreds of gang members gathered outdoors as the Warriors wend their way through the crowd. Cyrus steps forward to address the gangs, and the plot soon ignites.

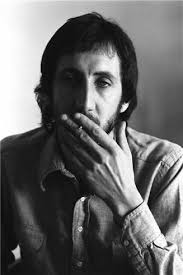

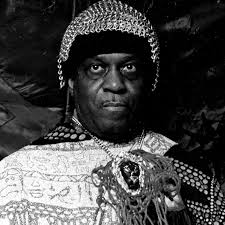

Roger Hill as Cyrus. Image via warriorsmovie.co.uk.

The film's introduction may not refer to future plot points, as the newsreel at the beginning of Citizen Kane does, but it teaches the audience the simple rules of the story premise and sketches in the landscape. Rival gangs and a long trip across the length of the city stand between the Warriors and their safe arrival home.

Thank you for reading.