In the two previous posts, I suggested that artists do as little talking as possible as they listen to feedback and process it through their intuition.

When a particular piece of feedback does not resonate intuitively, sometimes it pays to ask questions. The resulting conversation may reveal that the critique in question had misstated things.

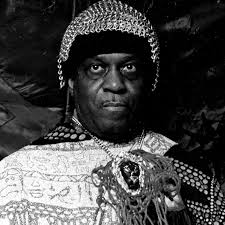

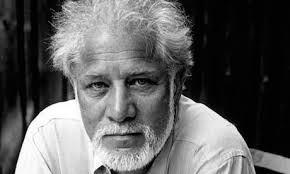

A great example of this is found in The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, Michael Ondaatje’s book of interviews with film editor and sound mixer Walter Murch. In this excerpt, Murch relates how the producer of the Godfather (for which Murch mixed the sound), responded to composer Nina Rota’s music score.

Murch: There was an intense crisis with the music. When Bob Evans heard Nina Rota’s music, he felt it would sink the film, that it was too lugubrious and didn’t have enough energy. . .

Ondaatje: You mean the main theme music?

Murch: Yes . . . well, all the music.

Ondaatje: My God, it’s a trademark!

Murch: Well, nobody knew that at the time. Remember, someone at MGM wanted to cut “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz.

(Murch told Ondaatje that Evans actually wanted to replace Nina Rota with Henry Mancini, to give the score more of an American flavor.)

Murch: Frequently what happens in film is that people, especially distracted executives, will say, I hate—pick one—the music, camerawork, art direction, acting in your film. But if you actually get under the skin of that prejudice, you can discover the particular thing they really hate — the pea under the mattress. It often comes down to one or two small things that spoil everything else. When I talked to Bob Evans, it turned out he hated the music for the horse’s-head scene, where Woltz pulls the sheet back and the severed head of his half-million-dollar horse is revealed in the bed. Maybe because Woltz is the head of a studio and Evans was the head of a studio and it’s a particularly striking, grisly scene—the first violence in the film—he felt the music should be appropriate to that.

I tried to listen to what Nino had written with Bob Evans’s ears, and I thought he had a point. The music, as it was originally written, was a waltz and it played against the horror of the event. It was sweet carousel music. You were seeing those horrible images, but the music was counterpointing the horror of the visuals. Perhaps it needed to be crazier a little earlier . . .

. . . You now heard, superimposed on each other, things that were supposed to be separate in time. So it starts off as the same piece of music, but then begins—just as Woltz realizes that something is wrong—to grate against itself. There is now a disorienting madness to the music that builds and builds to the moment when Woltz finally pulls the sheet back.

We played this version for Evans, and he thought it was fantastic. . .

The result was that some of the heat was taken off the music.

Michael Ondaatje, The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, pp. 99-102